By Mike Dibb (Seeking approval from the author)

My encounter with Budd Boetticher’s films involves two times and two places, separated by more than thirty years. The first time was 1960 and the place Trinity College, Dublin; the second was 1992 and the place was Lone Pine, California. In the meantime, I have learnt how to pronounce his name correctly – Be-ti-ker – and have met and talked with the man himself at his home near San Diego. These personal details are important. Too often we like to discuss movies, or for that matter books and paintings-as if they exist out there with a value and a meaning that can be disentangled from all the connecting tissue of thoughts, feelings and personal circumstance that surround our engagement with them.

1960 was the year in which I discovered American cinema, or rather discovered that I could take it seriously as well as enjoy it. This was just before television took over, when Dublin allegedly had the highest per-capita rate of cinema-going in Western Europe. Every cinema had a double bill that changed three times a week. I was introduced to Cahiers du Cinéma, which was heavily into auteur theory and American movies. ‘King Arthur’ was the emphatic title of Jean-Luc Godard’s revue of Arthur Penn’s The Left-Handed Gun – heady stuff and a lot more interesting than my academic studies. My most important acquisition, however, was a copy of Vingt Ans Cinéma du Américain, edited by Bertrand Tavernier. It was brought over from Paris by a friend and, as we scanned the Dublin evening papers together, it seemed that almost every Hollywood movie mentioned was in continuous circulation.

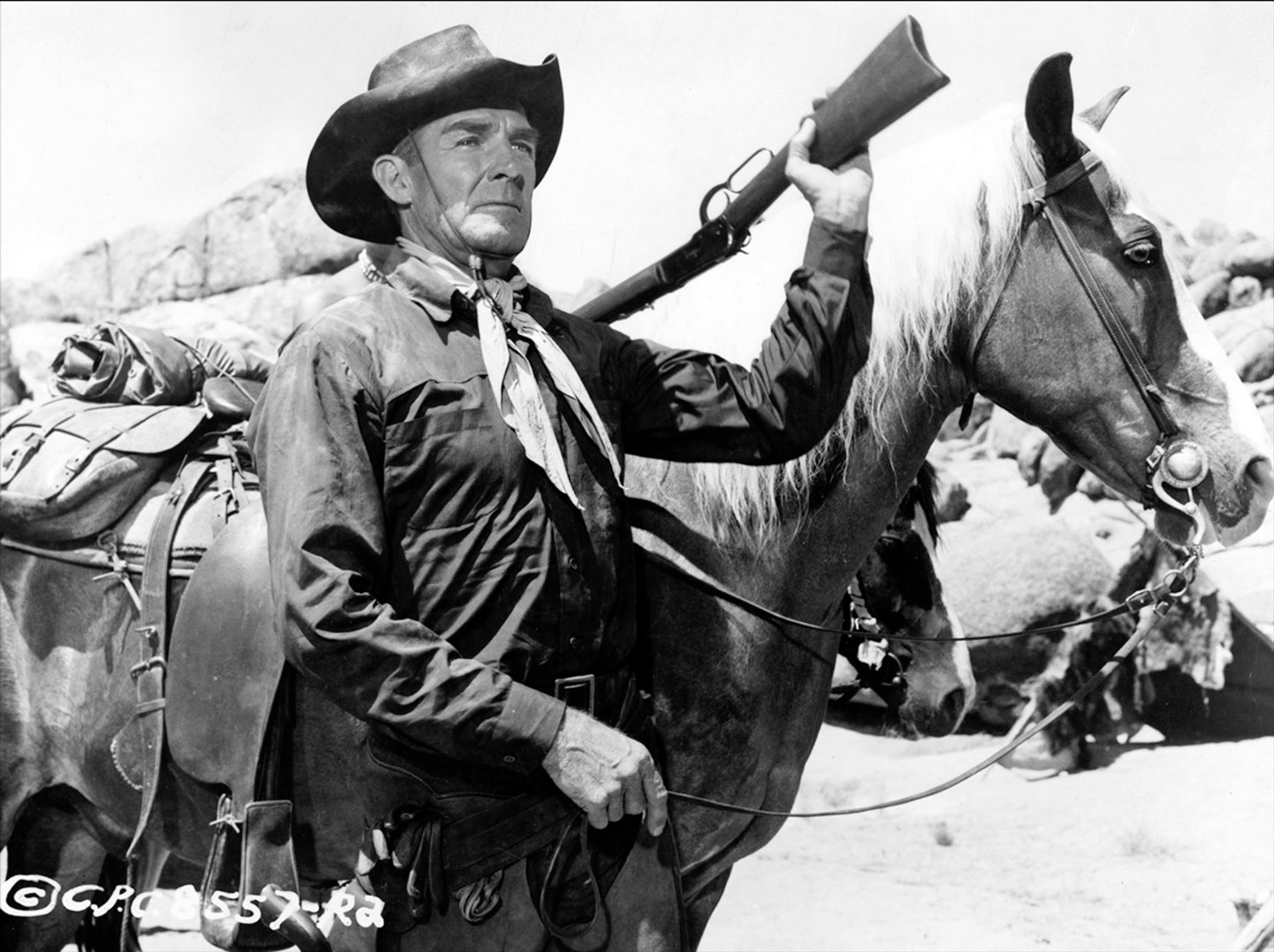

I had been seeing Hollywood movies every week of my life since the age of eight. As a family we went to the cinema regularly and my father, being a systematic man, kept a little book with a list of films look out for, based on the reviews of The Observer film critic, C.A. Lejeune. She was, I seem to remember, rather patronising about Westerns unless they were obviously presented as ‘significant’, which often turned out to mean portentous; the rest went into the category of ‘horse operas’, a term which now, when separated from C.A. Le J.’s dismissive connotations, I rather like. It emphasises the horse as the lyrical centre of the Western; it also underlines the importance and pleasure of encountering again and again the Western’s particular mythology and stylised forms of presentation: of action, character, speech, violence and, not least, music, so often neglected but always so potent. And this is where Budd Boetticher comes in. I cannot think of another director whose films take the simplest and most archetypal conventions of the genre and rearrange them in such a playful, intelligent and unpatronising way. The first two films I saw were Comanche Station (1960) and Ride Lonesome (1959), two of the four films (Seven Men from Now, 1956, and The Tall T, 1957, were the others), that Boetticher made in collaboration with the writer Burt Kennedy, actor Randolph Scott, producer Harry Joe Brown and, as I now realise, the landscape of Lone Pine. Together these films form a unique quartet, a set of themes and variations on roughly the same story and with roughly the same number of characters, made within a four-year period from 1956 to 1960, and all of them shot in the same place. This quartet has a unity that sets it apart from Boetticher’s other work, and these are the only films of his to which I want to refer.

Of course, when I see them again today I see them differently. I first watched them on a wide screen in a big cinema; indeed I was introduced to Boetticher’s films by Charles Barr, who at that time was preparing a postgraduate thesis on CinemaScope. Nowadays, apart from very occasional outings at specialist cinemas and festivals, the films turn up at odd times on television, which is where I have had to catch up with them, unsatisfactorily scanned and visually diminished to fit the small rectangular format. I have now visited the location where all four films were made, and I realise how important it was. Lone Pine is a small, two-motel town in northern California, a three- to four-hour drive from Los Angeles. Nearby, in the few square miles between Lone Pine and the road up to Mount Whitney, is an unusual outcrop of boulders and canyons called the Alabama Hills. For over seventy years, it has been one of Hollywood’s favourite locations, and several hundred films have been made there. From time to time, this landscape has stood in for India, Texas, Mexico, Peru and Argentina. But ever since the first silent film crews went there in the 1920s, it has been used as a location for Westerns, from small-scale series like The Lone Ranger to the massive How the West Was Won. Tom Mix, William Boyd, Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, Tim Holt, John Wayne and Clint Eastwood are a few of the many male heroes who have galloped to the rescue around the same rocks. Lone Pine is a magical place, at once both intimate and epic. Significantly, the only way to traverse it is on foot or by horse. In the daytime, under a hot sun, it seems to present itself as a natural location in which to tell a story, and what better story than a Western. In the evening, it takes on another kind of mystery. You can walk across the rocks by moonlight without the aid of a torch and, as you do so, feel yourself part of a day-for-night sequence.

It is also a wonderfully economical location, the perfect place for tight schedules and small budgets. You can put a tripod almost anywhere and, spinning the camera through 360 degrees, pick up a variety of different shots, each beautifully lit, particularly in the early morning or late afternoon. No wonder so many people came. But, for me, no-one before or since has exploited the dramatic potential of this place more lyrically and effectively than Budd Boetticher and his various cameramen. His are the quintessential films about being in Lone Pine. The fact that so many people had been there before was in a sense a help. The place is alive with the sounds and memories of drifting cowboys, laconic dialogue, galloping posses, gunshots, campfires, stagecoaches and hold-ups. There is an early exchange in Ride Lonesome which seems to me to speak both for the characters and the filmmakers: ‘A man needs a reason to ride this country – You gotta reason? -Seemed like a good idea.’

Because Lone Pine is a place where so many of the stereotypical images of the Western have been located, it became for Boetticher and his writing collaborator Burt Kennedy the perfect place in which to rework the conventions of the genre in a playful and imaginative way. Randolph Scott’s expressively inexpressive face echoed the stones. He and his horse could emerge out of this landscape at the start of the film and return back into it at the end. In Comanche Station, the last of the cycle and I think formally the best, this happens within exactly the same frame of the Alabama Hills against a backdrop of Mount Whitney. Scott enters right to left at the beginning and exits left to right at the end – at once both economical and elegant. As Budd himself confirmed when I met him: ‘The great thing about Lone Pine is that you don’t need to go anywhere else . . . we had sand, desert, a river, mountains, all the volcanic structures, it’s amazing – it looks like it was built there for movies . . . Burt Kennedy and I just went from one place to another rewriting scenes to fit the rocks which is what you should do.’

The beginning of Comanche Station is also a very good reminder of how much happens visually within these films. Nothing is said for several minutes and when the dialogue comes, it is sparse, even a little familiar: ‘Alright, Lady, What’s your name? -Nancy Lowe – I should’a known – Why d’ya come? – Seemed like a good idea.’ Seeing any one of these films reminds you of the others. For instance, some scenes seem almost interchangeable, odd lines of dialogue get repeated; what looks like the hanging tree from Ride Lonesome turns up in the middle of the river in Comanche Station. But, in the case of these four films familiarity elicits pleasure rather than contempt – indeed it is often one of the mainsprings of the humour. Burt Kennedy obviously enjoys the use of conversational patterns, in which certain words and phrases are repeated almost like rhyme: ‘Like you, for instance? – Like me, in particular . . . Sure hope I amount to something. – Yeah, sure was a shame. – Shame? – Shame that my pa didn’t amount to anything.’ He also likes the familiar archaisms of Western speech, so of course all the women – there is only one in each film – are referred to as ‘Ma’am’, people are always ‘obliged’ to each other, and everything that Scott plans he `full intends to do’.

The films consist of alternating scenes of action and dialogue, movement and repose. Boetticher loves horses, and much of the lyricism of the films comes from his pleasure in the rhythms of riding through varieties of landscape. Almost everything happens in the open air. An isolated swing station or a cave in the rocks is the closest we get to a social space; elsewhere it is the campfire and the coffee pot (indeed it confirms the general truth that in the Western the cup of coffee is as important a focus of social interaction as the cup of tea in British cinema). Boetticher also loves the rhythms of speech and elicits vivid performances from his actors.

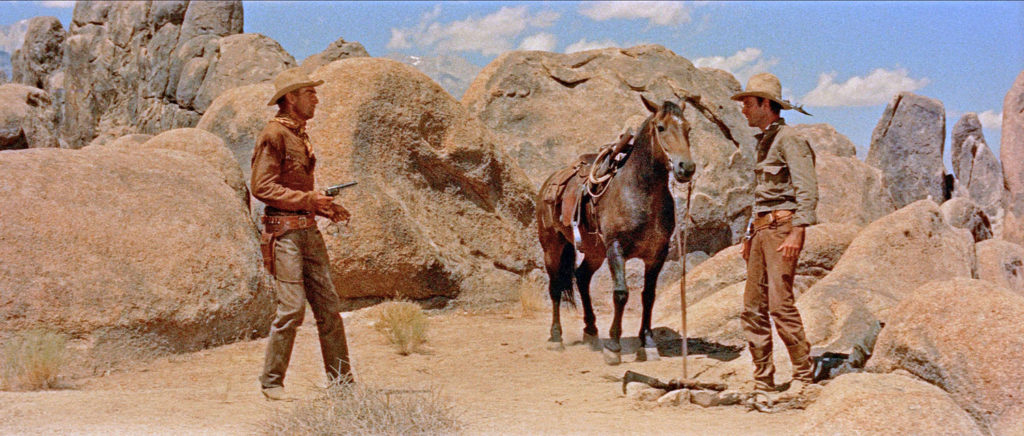

The lines are as well choreographed as the action, to bring out every nuance of irony and humour.’ The villains were the stars in my films’, said Budd. ‘They stole every film they were in.’ In fact, having found so many good new actors is one of the things of which he is most proud. Lee Marvin, Richard Boone, Henry Silva, Craig Stevens, Richard Rust, James Best, Claude Akins and James Coburn all cut their teeth in his films, and were often given their opportunity to shine through the generosity of Randolph Scott. He was the still centre around which the mayhem revolved. ‘Every picture he would let the villain upstage him!’ Boetticher told me, adding that when James Coburn made his first appearance in Ride Lonesome, Scott was so impressed that he insisted on more scenes being written for him, and these became some of the best and funniest in the film. `Young . . . mostly’ is the characteristic reply of one Young Gun when asked his age. There is always a pair of Young-mostly Guns in each film, social orphans with ‘no folks, no schoolin”, who dream of amounting to something and are often surprised by emotion: ‘One day I’m going to get me some land, and I’m going to have pigs, cattle and chickens, and I’m going to be a fanner . . . and do all the things I’ve ever wanted to do and you know something? We’re going to be partners right down the middle – We are? – Yeah . . . Jim, how long have you and I been riding together? – Four years maybe? – More like seven . . . don’t you know that I like you? – No, I never knew that!’ They are also surprised by each other’s achievements: ‘I didn’t know you could read, Dobie – Well, Frank, I ain’t much with books and newspapers but plain words, y’know, like signs, wrappers and such I do pretty good!’ Always, they are attached to and dependent on a no-good but charming father figure, who they begin to mistrust, rightly as it turns out, as they always die. Death is the risk that everyone takes in a world where cowardice and shooting someone in the back are the worst crimes; but death is always quick, and there is rarely much blood.

Boetticher is clearly not much interested in history or communities. His world is a long way from John Ford’s and closer to but less rugged and complex than that of Anthony Mann. For Boetticher, the Western is perfect as a terrain for fables, preferably set in a landscape that is everywhere and nowhere, `Once upon a time there was a man . . .’ He shows no moral or sociological concern for the historical roots of the conflicts between the indigenous Indians and the White settlers. Indians are not individualised, rather seen as an abstract threat, just another problem to be overcome or another way to lose your life. In this cycle of films, everyone is a loner, and the Randolph Scott character is the loneliest of all. The difference is that his loneliness is chosen; he is a man with a mission, albeit a private one, morally ambiguous and often wrongly bent on vengeance; he is driven ‘to do what a man has to do’, but is pretty pessimistic about the outcome. He is opposed by a man of the same age who is is alone because he has stepped outside the law. The two always seem to know each other from the past and know more about the other than each would like. This can become the pivot for simple moral dialogues on the ironies of fate and also the trigger for much of the action as each tries to out-manoeuvre the other.

The other trigger for the action is, of course, the fate of the woman. In these very male films, and in common with most Westerns, there is absolutely no risk of political correctness, and stereotypes abound. Whereas, ‘A man does one thing in his life he can be proud . . . a woman should cook good.’ Women are the objects of unconsummated desire, but beyond that a bit of a mystery: ‘The way I look at it a woman’s a woman, ain’t that right Frank? — If you say so!’ Boetticher’s interest in Spanish/Mexican culture expresses itself throughout his films, not least in the way women are seen. His values grow out of the cultural tradition in which the male code of honour is a driving force and from which Don Juan was born. As he said of himself: ‘I was the worst macho in the world but I hate the word.’ His films are directed with the puritanism of the hellraiser; a cleavage, a torn blouse, a discreet wash in a river and a rare kiss are the nearest one gets to explicit sex. On the surface, women may appear to have a central importance: they are dreamed about, desired, even fought over but . . . they are never seen for themselves. They are really just tokens in what are always struggles between men.

Another key Hispanic influence is the bullfight, an activity whose meaning is also defined, like the Western, by shared rituals and codes of behaviour. As a young man, Boetticher was also a boxer and athlete. In all these activities, professionalism is essential to a sense of self worth, any visible hint of cowardice is unacceptable, everything must be accomplished with dignity and grace. These are the virile attitudes and moral values which pass seamlessly and effectively from the closed world of Budd’s sporting arenas to the closed world of his Westerns. They are the attitudes that still sustain his lifestyle. When I went to see him, we met in the stables of his small ranch near San Diego. On the wall were stills from some of his films alongside photographs of his bullfighting friends. Together with his wife, he rears a rare breed of Portuguese horses, which are powerful and beautiful. Nearby he has a small arena with a half-moon, colonnaded stand of seating forming a miniature bull ring in which he can train and ride his horses. Despite his age, Boetticher is still a strong man, which obviously matters to him. As I watched him interacting with his horses, I could feel the existential pleasure which this kind of activity gives him. I was also very much reminded of the horse-roping and bull-riding scene in The Tall Tin which Randolph Scott’s ageing virility is put to the test. Like all physical and sporting rituals, the contest can seem at one level pointless, even faintly ridiculous. On the other hand, at its best, it can be significant and thrilling.

I can never recover the excitement of first seeing these Boetticher Westerns. Watching them again, I find them thinner than they seemed then, and some of the stereotypes are not entirely redeemed by irony and humour. But, having now encountered the generous energy of the man and visited Lone Pine, I feel I understand the source of their vitality. In a very particular way, the films are a direct expression of the strengths and limitations of the men who made them. The camaraderie and humour involved in their making still comes through in the playing. And throughout all four films, there is always the landscape around Lone Pine, effortlessly photogenic, skilfully deployed without a hint of self-conscious artifice.

It also seems to me that the time when this quartet was made is important. In the late ‘fifties, it was still possible to make this kind of small-scale independent film. Very soon, television was going to change the landscape of cinema, and very soon the Western itself was going to be in trouble, torn between the twin stools of too great a naivety and an over-aware sophistication. Budd Boetticher and his team arrived just in time to manage this balancing act pretty well . . . or pretty well, mostly.

In 1957, having just seen Seven Men from Now, the great French critic Andre Bazin wrote the first and still possibly the best piece about Budd Boetticher and, as he had the first word, it is perhaps appropriate for him to have the last: ‘The fundamental problem of the contemporary Western springs without doubt from the dilemma of intelligence and innocence . . . [In Seven Men from Now] there are no symbols, no philosophical implications, not a shadow of psychology, nothing but ultra conventional characters engaged in exceedingly familiar acts, but placed in their setting in an extraordinarily ingenious way. with a use of detail which renders every scene interesting . . . even more than the inventiveness which thought up the twists in the plot, I admire the humour with which everything is treated . . . the irony does not diminish the characters, but it allows their naivety and the director’s intelligence to co-exist without tension. For it is indeed the most intelligent Western I know while being the least intellectual, the most subtle and the least aestheticising.’

It is very perceptive, an exemplary piece of film writing. What Bazin wrote about Seven Men front Now applies to the other three films that followed it. Bazin also understood how, in a genre of filmmaking that is as full of conventional stereotypes and narrative devices as the Western, freshness and originality often come from imaginative reworking and respect for the familiar. He also understood, in a way that some of his fellow writers at the time did not, that authorship is a collective enterprise. Boetricher’s Ranown cycle owes a great deal of its success to the fact that it was one of those rare moments when the right group of people managed to come together at the right time and place. The ground rules were set but, exploiting rather than resisting the limitations, Budd and Co found an unusual degree of harmony and freedom. And in Lone Pine’s Alabama Hills they found the perfect setting in which to invent and improvise their short series of four memorable chamber Westerns.